”

Written byNatalie Fraser

Miliswa Mbandazayo’s Debut Work Addresses Our Betrayal of Black Women.

In the midst of a tumultuous storm, Luxolo and his physio-turned-mistress, Chelsea, escape the city for a hedonistic night away from their realities. However, their plan for a steamy and subtle getaway is turned on its head after an altercation that renders Luxolo unconscious. A knock on the door leaves her no choice but to hide him in a cupboard before letting in who she assumes to be the domestic worker. Chelsea pays her no mind and continues in her panic, completely unaware that the woman standing in the room with her is the owner of the house, a high-powered figure in finance, and Luxolo’s wife—Babalwa. As the storm rages on, the three are trapped in the house and forced to reckon with each other, themselves and the decisions that have brought them to this point.

What ensues is an absorbing, thought-provoking, and often laugh-out-loud-funny play that boldly confronts the audience and our society’s apathy towards the pain of black women.

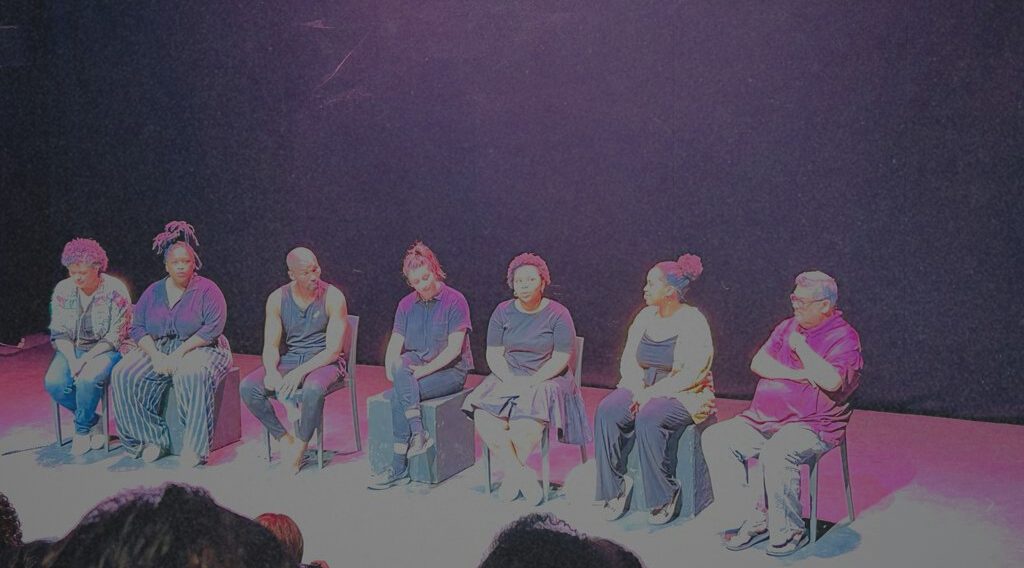

To Throw A Brick is the debut play of Miliswa Mbandazayo, who started writing the play in 2020, her final year of university. In 2023, she revisited the work and was one of five writers chosen for the NATi Jong Sterre Jakes Gerwel Playwriting Residency, a three-week mentorship programme for aspiring playwrights. A year after its first staged reading as part of the 2023 New Voices programme, the play is being staged at New Voices for three nights as a fully produced play directed by Faniswa Yisa.

“What ensues is an absorbing, thought-provoking, and often laugh-out-loud-funny play that boldly confronts the audience and our society’s apathy towards the pain of black women.”

The story, particularly Babalwa’s, is the one that Mbandazayo found herself returning to often since first writing it in 2020. The story is one that she had seen play out in the lives of black women around her, time and time again—that of a black woman being tossed aside for or by a white women, being left to pick up the pieces of other people’s poor decisions and the all too common occurrence of being assumed as “working there”, her presence needing to be a service to others, rather than simply belonging without the need for justification.

“As I was experiencing challenges as a black woman in Cape Town, I realised so much of it is gendered and racialised, especially when it came to romantic relationships,” says Mbandazayo. When sharing her frustrations with female relatives or friends, she was met with a recognition of the difficulties of being a black woman but also with a sense of resigned acceptance, especially when it came to cheating partners.

“It was something you either had to accept and live with, or you had to be content being alone for the rest of your life,” she says. “This angered me, it hurt and frustrated me. I want better for myself, my loved ones—for black women! We deserve that. So, this story stemmed from trying to make sense of that whilst also wanting to nuance it and speak to some of the unique struggles black women face. To answer questions like, can we find love that doesn’t need to be endured, that doesn’t come at the cost of suffering.”

Mbandazayo skillfully manages to set up the play as a gasp-worthy, fun premise that holds the potential of being a soapie- or reality-tv-show-esque relationship drama that we can’t tear ourselves away from. Just as the audience is settling in for a straightforward hour of entertainment, she pulls the rug out from under your feet and you are struck with the simple reality of the work and are unable to turn away from the mirror it is being held up in front of you. She manages to unite the audience in captivating narrative while, at the same time, dividing it into those shifting uncomfortably in their seats and those nodding along, relieved to see themselves being seen (especially by those shifting uncomfortably on their seats).

“I want to tell this story because all three of the characters are not extraordinary,” says Mbandazayo. “Nothing that happens to them is extraordinary. That bothers me. It bothers me that a man can cheat on his wife and treat his mistress like a plaything. It bothers me that society finds new and sinister ways to disrespect black women. I’m telling this story because I want to show this and shout that black women deserve better. I want to explore the harmful effect this has on women. The betrayal of marital vows, the denial of humanity. When Chelsea and Luxolo pursue their desires, Babalwa must pay the price. Black women deserve better and deserve justice. Justice means joy and dignity for black women.”

“As I was experiencing challenges as a black woman in Cape Town, I realised so much of it is gendered and racialised, especially when it came to romantic relationships,” – Miliswa Mbandazayo

To Throw A Brick is a play that confronts and challenges but, with that, Mbandazayo wanted it to be a reclamation and expression of rage, an emotion that black women are so often shamed or even mocked for having. “I am an angry black woman. I reserve the right to refer to myself in that way. It has been made a trope and, in doing so, denies my humanity. I hope to redeem that with this play.”

In this debut work, Mbandazayo has achieved a gripping narrative that is as entertaining as it is poignant. I can only hope that it will have many runs in the future but, for the time being, don’t miss your opportunity to watch To Throw A Brick at the Artscape Arena from 23-25 October 2024.