”

Written byIndio Friedmann

“When I was thirteen, I didn’t understand why I couldn’t grow up to be Pamela Anderson.”

“HOW TO MAKE BOSOMS GROW: Massage for 10-15 minutes every morning and evening. Eat papaya and drink milk. Jump and down without a bra on. Exercise pectoral muscles (but not too much).”

This Pamela Anderson instructional manual is an actual page taken out of my grade 7 diary after thorough research through my Seventeen magazine haul. Alongside some cut outs of personality tests (I was a seductive field mouse in my past life by the way), there is an article where a 20 year old woman has been interviewed on her breast size insecurity. She admits this led her to book a breast enlargement surgery (erhm boob job) which she believed would make her happier. At the end of her interview is a final quote of hers, “No one should feel pressured to change their bodies so drastically.” Even more ironically, on the next page I stuck a smiling Paris Hilton and a random free workout guide I had found.

When I was thirteen, I didn’t understand why I couldn’t grow up to be Pamela Anderson. I was certain that as I grew, so would my naturally salon looking hair, curvaceous hips, an un-shy bust and of course my career as a certified baybe. Naturally, this didn’t happen judging by my curly black hair, fear of the ageing job security in being a baybe and yes, also the rest too. But, had artist Cara Biederman’s pieces been around back then, the Anderson illusion would have been rightly shattered. No more Barbie-watch. This is because much of Cara’s work is a satirical commentary on the commercialisation of beauty, which in turn creates an unrealistic standard to look up to. All those identifying as a woman within this particular context, will read familiar lines and see familiar scenes in her work as she turns beauty into the absurd and praise into ridicule. Further, her very material comes from actual magazine cut outs, as well as the thoughts we all have but choose not to say.

2012 Indio had no idea that ten years later she would encounter yet another interview with a 20 year old woman, however this time ridiculing the very beauty ideals that she had begun her womanhood with.

Cara is currently in her second year at the Cape Town Creative Academy. Even before her studies, she had begun finding her artistic identity within a little cartoon she created and described as somewhat of a loose extension of herself. She explains “This character brought me into my creative voice. I think because I could make all these little comics and situations with this one character but it was also things that other people were experiencing. In matric, I laid the grounding for my work about women and facetune and my final art prac was a 2m x 3m comic story about facetune.” Cara draws her inspiration from observing her own daily experiences as well as those of others. “I witnessed the rise of influencer culture and now, it is even more crazy than when I was 17, so I feel I will definitely keep doing this.” Artists such as Cindy Sherman with her recreated self-portraits and Lauren Greenfield with her documentary “Generation Wealth,” continue to also be a source of inspiration

Cara’s vision has continued to appear in more recent artworks, with a focus on conceptualising how “plastic surgery abstracts from the body” through a series of pieces. In one piece, she decided that she was going to turn herself into an influencer. She conducted a social experiment with a facetune series of herself, alongside natural photos and self-proclaimed influencers.

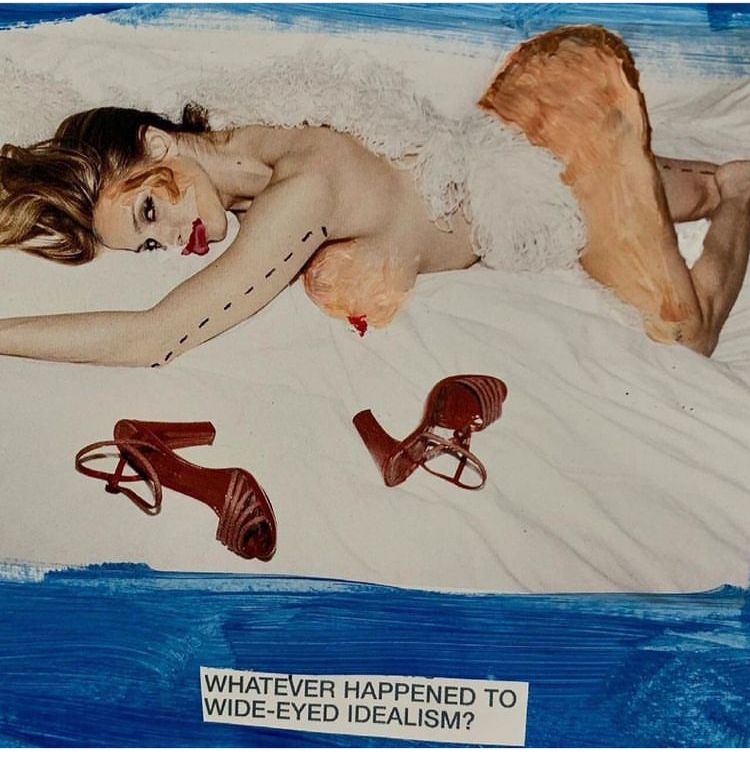

Surprisingly, her obviously accentuated features were met partly with praise by many men, and partly with distaste, by mostly women. Next she made a life-size sculpture of a woman. “I named her She. She is a 3D physical amalgamation of all the work I’ve been doing. She is huge, lifeless and really scary with a mannequin head and body made out of stockings and newspaper. I even gave her a BBL (Brazilian butt lift, obviously).” For me, the abstraction piece that I deeply connected with was her satirical zine called “Portrait of a Woman.” She says this piece speaks to “how women are trapped into being deathly afraid of aging & their ‘flaws’. I made these collages with images and text I found from magazines, recreating my own version with acrylic paint.” She details the journey when creating her piece; “When I started flipping through magazines to find text and images, I started to feel less excited. I was finding the media scary, in a laughable way though, like finding a quote in a magazine that says “It just breaks my heart when I see younger women look older than I do.” I started collecting these types of quotes and choosing images from these magazines to go with them. The aim was to morph the models’ bodies and faces to make a statement about how the media and plastic surgery abstracts women and make us think that the wildly unbelievable is in fact believable when it comes to appearance. So I started to paint on these women. I used acrylic paint to slim their waists, their noses, to add extra lip and cheekbone, and transformed them to be slightly horrifying to look at.”

“When I was younger, the type of feminism I grew up with was labelled as empowerment. But it wasn’t really empowering”

We can also sometimes be contributors of our own disempowerment. Cara exposes this as instead of just focusing on misogynistic men or an over idealistic society, she places you, the victim as also somewhat of an accomplice, at centre stage. Here, we see an overlap of what is expected of us and also what we are doing to meet this expectation. “When I was younger, the type of feminism I grew up with was labelled as empowerment. But it wasn’t really empowering. I always said to my mom that I’m going to get a boob job or a nose job. She always replied with no you’re not and that I must love and accept myself. And I would go shut up mum, I’m doing it for myself. When I got older, I realised this wasn’t true, I’m actually not doing it for myself. What was actually making me insecure were other people, not myself.”

On the other end, it is all very well to make a classic point in feminism and purposefully not shave but in reality it is its own antithesis. Catering to the male gaze is performative in nature which means that where there is positive conduct (the do), there is also negative conduct (the don’t). Getting a BBL might be positively contributing to the male gaze but intentionally not shaving is catering in opposition to the male gaze. It’s still relative to a misogynistic male’s viewpoint, not your very own. The logical fallacy here being men (generally speaking) tend to dislike hair on women, therefore if I do not shave, I am disavowing the male gaze.

So feminism to me is moreso about intention, I’m not shaving to have my legs perused by every Mathew I meet from Durban but I’m also not looking at my hair growth as a giant ‘fuck you’ to the patriarchy. Empowerment is just not enough, we need to move towards self-empowerment, independent of others. “Women’s bodies are commodified. It tripped me out, made me look at things differently because I always had this perception of empowerment, that we’re doing it for ourselves. But would this be happening if history went differently? Was I part of the problem? I thought that again and again, while I made these works, and oftentimes had to leave the studio and take multiple cigarette breaks to avoid the freaks I had created. That’s when I realised, it’s just art… It’s not that deep. But it was, I was lying to myself. The subject matter in these pieces will never not disturb me, but in an intriguing way, I suppose. I hope for these works to be looked at through a lens of humour, as well as a bit of sheer horror, so the viewer can feel what I felt while making them.”

Cara’s message is simple: “People are going to interpret your stuff however the fuck they want, so just do it. You don’t need a long artist statement of what this means or who you’re catering for. The art can just speak for itself.” And it’s true, you don’t need to acclimatise to what is or what is not expected from you as a woman. Your idea of femininity can speak for itself.

For more of our Visceral features, click here.